For the grass that you have just eaten, Oh goat,

Give us some good pashmina.

For the water that you have just drunk, Oh goat,

Give us some good pashmina.

Sit down on the grass and be still, Oh goat,

So that we can take out your pashmina.

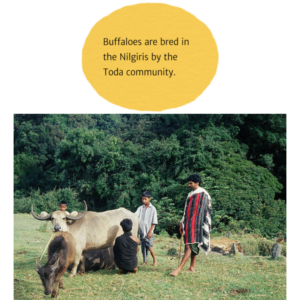

Goats being blessed – A monk blesses pashmina goats consecrated to the gods. Now that pashmina goats are important to the Changpa economy, they are well looked after and revered.

Changthang shivered through one of the most severe snowfalls it has experienced in more than 50 years. Changpa pastoralists saw nearly 24,000 goats perish in the cold – the highly valued pashm goats whose fine hair is one of the most expensive textile fibres in the world today! But this was not always so. As Monisha recounts, the elders from Changthang recall how their sheep wool was far more expensive than pashmina! However, once the borders with Tibet closed, Pashmina from the changthiang goats scaled in price and popularity, changing fortunes of these goats, who became the favoured one from the northern plateaus of Ladakh. Pastoralists made shifts in their livestock composition even as the stolid sheep has steadily lost favour in the gold rush for pashmina. Goats are slowly being stripped off the comfort of their wooly companions – the changthiang sheep – who were more in numbers and huddled around them in concentric circles, keeping the goats warm and comforted. The devastation of 2013 is a poignant tale of what happens when a pastoral product commodifies and tips the balance of their life world.

The goats are milked twice in the day, early morning before they set out to pasture and when they return. Neatly tied in two rows, the milk the animals produce form a large part of the Changpas’ diet as well as oil for the monastery’s offering lamps. Photograph Tsering Wangchuk Fargo.