Kalyan Varma

with Dhangars, Maharashtra

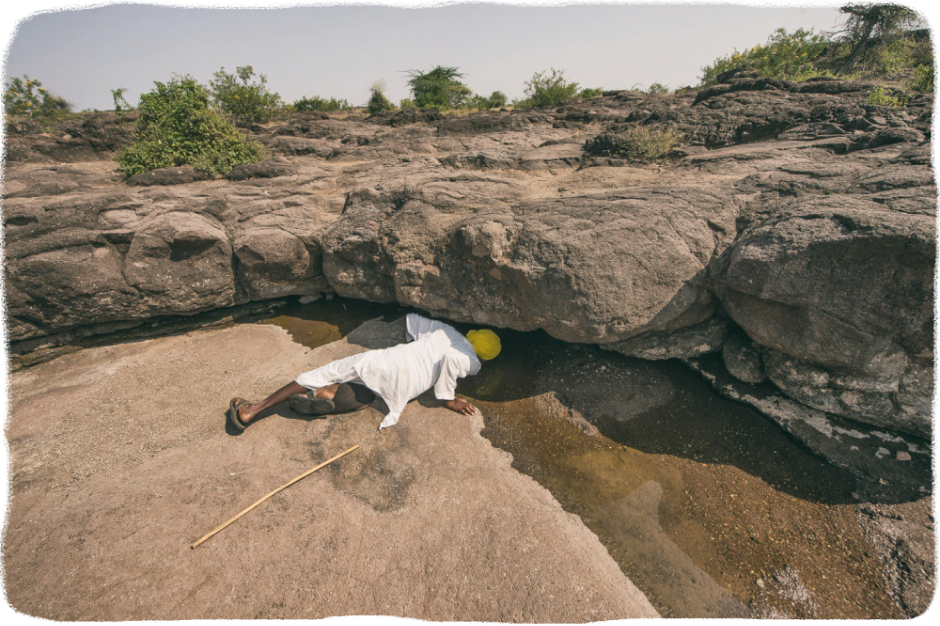

For the nomadic Dhangars, access to water is the key to their journey. They are aware that as they move, available water sources are likely to be contaminated because of the factories en route. Their only access to water will be the very few seasonal streams, scattered village wells and an odd irrigation canal. Like the sheep, they drink straight from the streams.

The Dhangars, even with hundreds of sheep, know each and every individual and spend time every day tending to them and caring for those with problems. In this case, one of the elders helps a lamb breathe just after it was born as the mother looks on.

Dhangars are one of the last migratory shepherding communities in India. The men take the livestock out for grazing taking a round-about route from one camp to the next; while the women pack up and load the household on horsebacks and take the shorter route to the next destination.

The landscape that the Dhangars use is one of the richest places for predators. In fact, recent research has shown that a lot of these predators depend on livestock and without the communities like the Dhangars, these grasslands would not support so many predators. Clockwise from top: A Jungle cat tries to hunt a rodent; A hyena with its pups in the grasslands; An Indian fox; A pack of wolves in Dhawalpuri grasslands.

These are the images shot using a thermal camera near the Dhangar livestock in the night in Dhawalpuri. Clockwise from top left: A wolf waits in the background as the Dhangars cook their dinner; A hyena walks past the sheep pen. The hyena is mostly a scavenger and depends on wolves to do the hunting; A wolf steals away a young lamb from the pen. They have to take and run away before the guard dogs come and attack them; Through the night, as the predators come to steal the sheep, the guard dogs keep chasing them away.

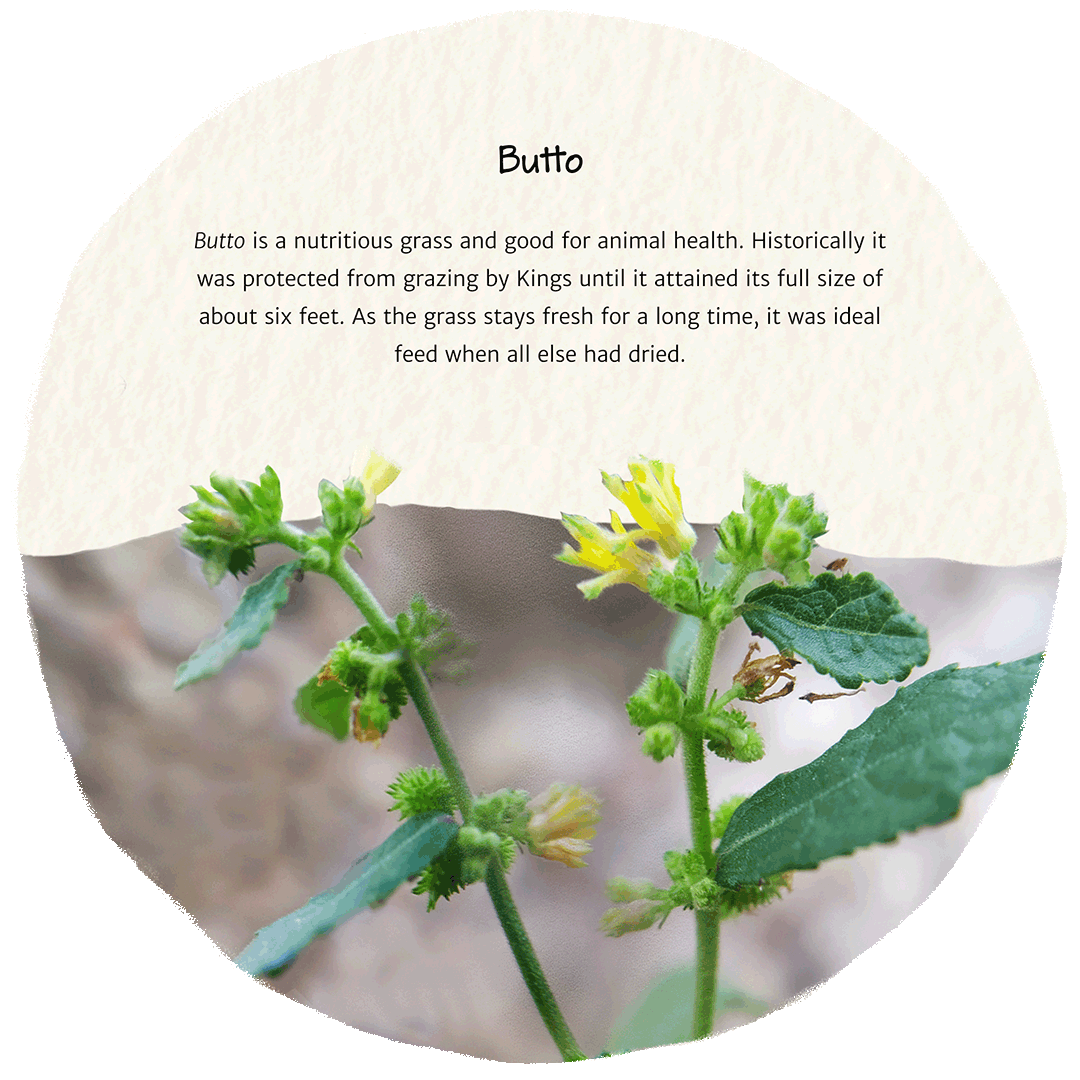

One of the chief predators in the dry and deciduous grasslands of the Deccan plateau. Ravaged by development infrastructure, real estate, cotton and sugarcane farming, the grasslands have shrunk, taking with them a large population of the wolf. Far from rejoicing, the Dhangars say they are left poorer; The wolves, they say kept them in balance. Taking away the weak ones, and keeping the herds trim. For shepherds of the Deccan plateau, a lamb lifted by the wolf is accepted as an offering to the gods; even a visitation from the divine. The Kuruma shepherds of Telengana, for instance, consider wolves to be ‘lakshmi’, the harbinger of wealth and good luck.

The livelihoods and shepherding methods of Dhangars are tied into folklore and stories and before every major move; they have ceremonies where they feed sheep to all their neighbours and associates.

Dhangars share the landscape that they use with wildlife. These community grasslands act as refuges for the animals and the livestock are prey for the predators. Although the shepherds lose many to wolves and other animals every year, they do not retaliate and feel that the predators being there is actually good for the health of the grasslands and their livestock.