Ishaan Raghunandan, with the Maldharis of Banni

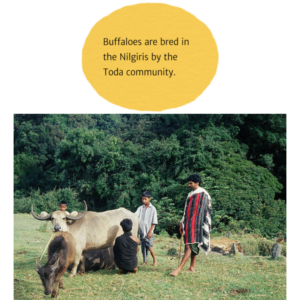

After the initial phase of photographing everything in sight, a deeper urge emerged, to use photographs as a means of communication with the outside world. And they began to photograph the things they wanted the viewer to see; the story they wanted us, urban dwellers, to know.While they have stuck to their traditional livelihood, modernity is fast catching up with Kachchh and its people. Many Maldhari children, exposed to the world working at factories or tourist hotspots, are exposed to so much more information than their parents or grandparents ever have been. In many ways we are more ignorant of their lives than they are of ours. Some of them aspire for a steady and risk free income, which requires much less effort than herding animals. Why shouldn’t they?

Ishaan Raghunandan is a professional photographer with a post graduate diploma in professional photography and an engineering degree. He works in the field of wildlife conservation and rural documentary. In the last four years he has worked towards using the power of photography to have a direct and visible effect on good social causes particularly in combating inequality in all its forms promoting freedom, education and environmental protection. He is actively involved in education, teaching photography in rural areas of Kachchh, while also instructing courses on Tropical Field Biology in Peru.

The grit and determination of ordinary people who achieve extraordinary things, while making the best of local conditions whilst living in harmony with the environment have inspired him to continue working in the field of conservation.